Causes of Amputation: Diseases & Risk Factors

Amputation is a word that tends to stop conversations mid-sentence. Even if it’s not happening to us, it brings up fear, questions, and a lot of “how does it get that far?” The truth is, amputations usually don’t come out of nowhere; they follow patterns we can learn.

Most people picture a dramatic accident, and yes, trauma can absolutely be a cause. A traumatic accident, such as a workplace mishap, motor vehicle collision, sporting event, or military conflict, can result in sudden, unexpected limb loss with both physical and emotional impact.

But many amputations happen after a long stretch of problems that were quietly building, like poor circulation, nerve damage, or a wound that refused to heal. Once we understand the common pathways, it becomes much easier to spot warning signs early and take smart next steps.

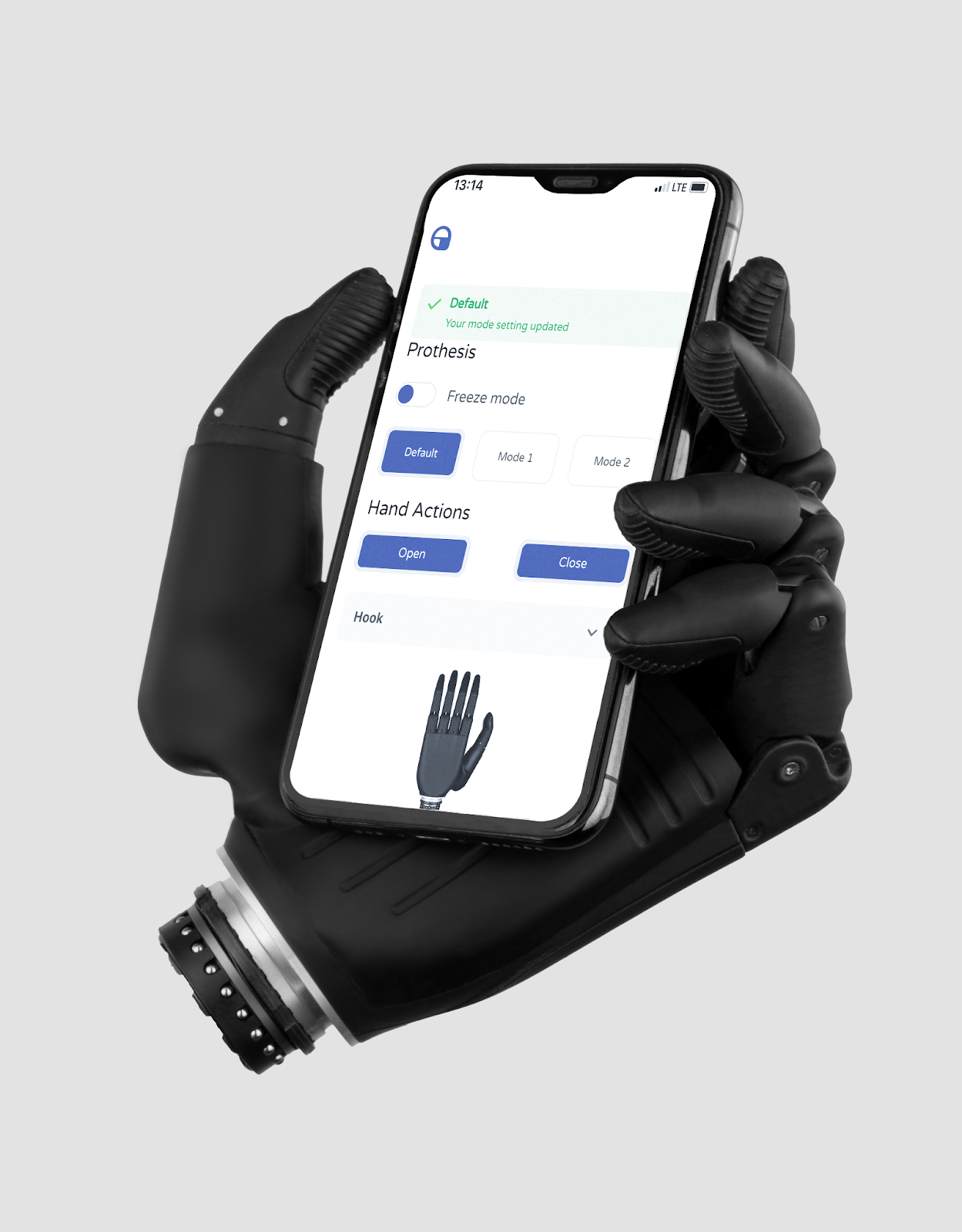

This article by Aether breaks down the major diseases that can lead to amputation, the risk factors that raise the odds, and what to do if something looks off. We’ll also touch briefly on what happens after an amputation, because many people reading this are thinking ahead about recovery and options like a bionic arm or other bionic prosthetics.

Physical rehabilitation is a key part of regaining function and adapting after limb loss, working alongside prosthetic options to support recovery. We’ll keep the explanations simple, non-graphic, and grounded in real-life situations people recognize. The goal is not to scare anyone; it’s to help us respond sooner and with more confidence.

What amputation means, and why it’s done

Amputation means the surgical removal of part of a limb, such as a finger, hand, or arm. It’s done when damaged tissue cannot be saved safely, or when keeping it would put the person at serious risk. That risk might be spreading infection, ongoing tissue death, or a tumor that needs complete removal.

Clinicians often describe amputation as a “last resort,” and that phrase matters. In plain language, it means the medical team has tried, or carefully considered, safer options first, like restoring blood flow, controlling infection, or repairing severe injury. If saving the limb is not possible or not safe, removing the affected part, while preserving as much healthy tissue as possible, can protect the rest of the body.

It also helps to say the quiet part out loud: amputation is sometimes a life-saving decision, not a “we ran out of ideas” decision. And if amputation does become necessary, it doesn’t mean the story ends; many people go on to rebuild daily function with rehab support and prosthetic options, including bionic prosthetics.

When infection is spreading, circulation is critically low, or tissue is beyond recovery, time becomes a factor. The aim is to prevent bigger harm, not to win a toughness contest.

Two common pathways to amputation: slow build vs sudden event

Most amputations follow one of two storylines. One is the slow build, where disease gradually damages nerves and blood flow, and wounds struggle to heal.

In both cases, several risk factors, such as diabetes, peripheral artery disease, and infection, can contribute to the progression toward amputation. The other is the sudden event, where injury or rapid circulation loss makes the limb unsalvageable, ultimately resulting in limb loss.

The slow build

In the slow build, a small problem becomes a stubborn problem. Reduced sensation can hide injuries, reduced circulation can starve tissue of oxygen, and infection can take advantage of slow healing.

Peripheral neuropathy is a common cause of reduced sensation, especially in diabetic patients. Over time, what started as “just a sore” can become a serious risk.

A simple example looks like this: someone gets a small cut or blister and barely notices it. Because the area has less feeling, it doesn’t trigger the usual “protect it” instincts, and it keeps getting bumped or irritated. Weeks later, it’s still there, and now it’s infected.

The slow build is frustrating because it can feel unfair. A wound that would heal quickly for one person can become a long-term fight for someone with diabetes or poor circulation.

That’s why early care matters so much; we want to interrupt the chain before it gains momentum. Proper foot care is essential for preventing complications and reducing the risk of amputation in at-risk individuals.

The sudden event

In the sudden event, the timeline changes from weeks to minutes or hours. Severe trauma can destroy tissue and blood supply, and sometimes circulation stops quickly because of a blockage.

In these cases, traumatic amputation may occur as a result of the physical damage, requiring immediate intervention to protect life and prevent dangerous complications.

A simple example is a major crush injury from a motor vehicle accident or heavy machinery. If blood flow is destroyed and tissue is too damaged to recover, clinicians may determine that the limb cannot be saved safely. It’s heartbreaking, but the priority is survival and reducing severe infection risk.

Sudden circulation loss can also happen without an obvious injury. If blood flow stops abruptly, tissue can be threatened quickly, and delayed care can mean fewer options. That’s why sudden color change, coldness, or severe pain should be treated as urgent.

Disease-related causes: Poor blood flow (PAD and PVD)

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) happens when arteries become narrowed, reducing blood flow to tissue, most commonly in the lower limbs. Less blood flow means less oxygen and fewer nutrients reaching the area that needs healing. That combination can turn minor wounds into long-term problems.

Poor blood flow affects healing in a very practical way. Healing is a repair job that needs supplies, and blood is the delivery system. If the deliveries don’t arrive, the wound stalls.

The superficial femoral artery, a major branch of the common femoral artery, plays a crucial role in supplying blood to the lower limbs and is often involved in vascular disease affecting this region.

You may also hear terms like peripheral vascular disease (PVD) used broadly for circulation problems in the outer parts of the body. Regardless of the label, the core issue is similar: tissues are not getting what they need.

When circulation drops to very low levels, the risk of tissue damage and non-healing wounds rises sharply. In severe cases, PAD and PVD can progress to the point where lower limb amputation becomes necessary as a last resort.

What “critical limb ischemia” can mean

Critical limb ischemia is a severe form of reduced blood flow that threatens tissue survival. In plain language, it means the tissue is not getting enough blood to stay healthy, and damage can progress.

Acute limb ischemia, on the other hand, is a sudden, severe reduction in blood flow to a limb that requires urgent intervention to prevent tissue loss or even amputation. If the situation is not treated, tissue death can occur, and amputation may become necessary.

This is one reason clinicians take circulation checks seriously. They may check pulses, compare temperatures, or use imaging to understand blood flow. If blood flow can be restored, it can change the entire outcome.

PAD can also be sneaky because symptoms vary. Some people feel pain with activity that improves with rest, while others mainly notice slow-healing wounds or skin changes. If a wound is not improving and circulation issues are part of the picture, it’s a signal to get evaluated sooner rather than later.

Disease-related causes: Diabetes complications

Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of amputation mainly through a trio of troublemakers: nerve damage, circulation problems, and infection risk. Diabetic patients are at higher risk because neuropathy can reduce sensation, so injuries are missed or underestimated. At the same time, healing can be slower, and infections can become more serious.

This is how a foot ulcer can start small and become dangerous. A blister or sore can form from pressure or friction, and because it doesn’t hurt much, it gets ignored. Once the skin barrier is broken, bacteria have an easy doorway.

Diabetic ulcers, especially diabetic foot ulcers, are specific complications of diabetes mellitus and are a leading cause of lower limb amputations due to their high risk of infection and poor healing.

The frustrating part is that early ulcers on the affected foot can look unimpressive. They may seem like something we could “just keep clean” and move on from. With diabetes, that approach can backfire, because delays give wounds time to deepen and infections time to spread.

Why diabetes-related wounds escalate

When sensation is reduced, we don’t naturally shift how we use our hand or protect the area. That means the wound is often exposed to repeated stress while trying to heal.

Weakness or deformity of the intrinsic muscles of the foot can also contribute to ulcer formation, as these muscles are essential for maintaining foot stability and preventing deformities. Add slower healing and higher infection risk, and the wound can change quickly.

This is why clinicians focus on early assessment and consistent care. They may evaluate circulation, sensation, wound depth, and monitor wound healing, because those details change the treatment plan and are crucial for preventing complications. The earlier we address the problem, the better the chance of avoiding major tissue damage.

If diabetes is part of your health picture, the best strategy is not perfection; it’s consistency. Daily checks, fast treatment of cuts, and not waiting for pain to “prove” it’s serious can reduce risk. It’s boring advice, but boring beats preventable complications every time.

Disease-related causes: Infection, including deep infection and bone infection

Infection can start at the surface and then move inward. A wound may begin with a skin infection, then spread into deeper tissue, and in severe cases, reach bone. When bone becomes infected, it’s called osteomyelitis, and it can be difficult to treat.

If bacteria such as meningococcal or MRSA enter the bloodstream, this can lead to blood poisoning (also known as severe sepsis), a life-threatening condition that causes widespread infection and tissue damage.

Infections push clinicians to think bigger than the wound itself. The concern is not only the local damage, but also the risk of spread and severe illness. If infected tissue cannot be controlled or removed safely, amputation may be considered to protect the rest of the body by removing all diseased tissue and preventing further complications.

This is especially important when circulation is poor. When blood flow is reduced, it is harder for the immune system and medications to reach the area effectively, increasing the risk of severe sepsis as a potential complication. That makes early detection and early treatment even more valuable.

Necrotizing soft tissue infection

Some infections are rare but extremely aggressive, such as necrotizing soft tissue infection. These infections can spread rapidly and require urgent treatment. In severe cases, amputation may be part of stopping the infection and preventing life-threatening complications.

Major surgery may be required to control aggressive infections and manage extensive tissue, bone, and blood vessel involvement.

We do not need to be experts to respect the warning signs. If symptoms escalate quickly, the safest move is to seek urgent evaluation. Waiting for it to “settle down” can be the mistake that changes everything.

Red flags of severe infection

Severe infection tends to announce itself if we know what to look for. Spreading redness, swelling, warmth, drainage, fever, and worsening pain are common red flags.

A wound that suddenly smells bad, changes color, or deteriorates quickly deserves urgent medical attention. For severe infections, it is crucial to seek evaluation and treatment in a hospital setting, where advanced care and emergency interventions are available.

If you’re thinking, “Maybe I’m overreacting,” that’s often the moment to take action. It is better to hear “good news, it’s not severe” than to discover the problem after it has advanced. Early evaluation can preserve options.

Disease-related causes: Cancer and tumors

Amputation may be considered for certain cancers and tumors when removing the tumor fully requires taking part of a limb. In some cases, major limb amputation or amputation surgery may be necessary to achieve complete removal, especially when less invasive options are not feasible.

The goal in cancer surgery is complete removal, because leaving tumor tissue behind can allow it to grow or spread. During tumor removal, preserving as much healthy tissue as possible is crucial to facilitate future prosthetic use and maintain function. In those cases, amputation is discussed as a way to achieve clear margins and reduce risk.

It’s also important to note that many tumors can be treated with limb-sparing approaches, depending on their location and other factors. Limb salvage is often considered as an alternative to amputation, focusing on advanced surgical techniques to save the limb when possible.

Treatment decisions vary widely, and they are personalized, with amputation surgeons and orthopaedic surgeons playing a key role in planning and performing these procedures. The key idea is that when amputation is recommended for a tumor, it is typically for complete and safe removal.

We can keep this simple and practical: if a clinician raises the topic, it is because they are balancing tumor control with overall function and safety. Asking questions about options, goals, and expected outcomes is appropriate. Patients deserve clarity, not mystery.

Other medical causes that can lead to amputation

Some causes are less common, but still relevant because they can be severe. Frostbite is a cold injury where freezing temperatures damage soft tissue, sometimes permanently. Severe cases can lead to tissue death and possible amputation.

Severe burns can also lead to amputation in some situations. Deep burns may destroy tissue and blood supply, and electrical burns can cause extensive internal damage.

In the most severe cases, major lower limb amputations may be necessary to prevent further complications. When tissue cannot recover safely, amputation may be part of the treatment.

A sudden circulation blockage is another medical emergency. If blood flow stops quickly, tissue can be threatened in a short time, sometimes resulting in the creation of an amputated limb through surgical intervention. Sudden coldness, color changes, or intense pain are signals to seek urgent medical care.

Trauma-related causes: injury and accidents

Trauma-related amputations often occur after high-force injuries. Car and motorcycle accidents, machinery injuries, and severe crush injuries are common examples. In these cases, tissue may be too damaged to repair, or the blood supply may be destroyed.

Traumatic accidents can result in traumatic amputation, including upper extremity amputations and leg amputation, depending on the nature and location of the injury.

Trauma decisions are usually made with survival in mind. Clinicians weigh whether the limb can be reconstructed safely and whether infection risk is manageable.

When they recommend amputation, it’s often because the alternative carries a higher risk of severe complications. The surgical decision may involve the upper leg or lower leg, depending on the extent of the injury and the best chance for recovery.

It can help to understand how quickly trauma can change the situation. Severe injuries may lead to major blood loss, shock, and an increased risk. Emergency teams focus on keeping the person alive first, then on preserving function as safely as possible. After amputation, a prosthetic limb can play a crucial role in restoring mobility and improving quality of life.

Risk factors that increase the chance of amputation

Risk factors do not guarantee outcomes, but they do stack the deck. Some risk factors are modifiable, meaning we can influence them with habits and medical care. Others are related to health history, and they tell us to be more vigilant.

Here are the risk factors that most often show up in the background.

- Modifiable risk factors

- Smoking which damages blood vessels and worsens circulation

- Uncontrolled blood sugar increases the risk of neuropathy and infection

- High blood pressure and high cholesterol, which raise the risk of poor circulation

- Delayed wound care, waiting too long to treat cuts, blisters, or ulcers

- Medical and historical risk factors

- Diabetes, PAD or PVD, and heart disease

- Kidney disease

- Neuropathy, reduced sensation that hides injuries

- History of ulcers or prior serious infections

If you see several of these on the same list for one person, that’s not a reason for panic. It is a reason for a stronger prevention plan and a faster response to any wound. After amputation, monitoring the contralateral limb is crucial, as it is at higher risk for complications and potential amputation, especially in patients with vascular disease and diabetes.

Additionally, the condition of the residual limb plays a key role in recovery and successful prosthetic fitting. In this area, speed and consistency beat willpower and good intentions.

Warning signs to take seriously

Our bodies usually give clues when something is wrong, even if the clues are subtle. A sore that doesn’t heal is one of the biggest warning signs, especially if it lingers for weeks or keeps reopening. Numbness, loss of feeling, and unusual color or temperature changes are also important.

Some signs are more urgent because they can signal infection or tissue death. Black or gray tissue, a foul odor, or fast-spreading redness and swelling should not be ignored. Fever, drainage, and pain that keeps getting worse instead of better are also red flags.

If you’re not sure what you’re seeing, that’s normal. Most people are not trained to judge wound severity, and that’s why clinicians exist. When in doubt, earlier evaluation is the safer bet.

After amputation, some individuals may experience 'phantom limb', 'phantom pain', or 'phantom limb pain', which are sensations or pain perceived in the missing limb.

What to do next: practical steps that help in real life

We do not need a perfect routine; we need a reliable one. The goal is to catch problems early, treat them properly, and reduce the factors that make healing harder. Here’s a practical playbook that is simple enough to stick with.

- When to seek urgent care

- Go urgently if a wound is rapidly worsening, there is fever, redness is spreading, or the tissue looks black or gray

- Seek prompt care if a wound is not improving, especially when diabetes or circulation issues are present

- What clinicians may check

- Circulation, including pulses and sometimes imaging to assess blood flow

- Infection signs, wound depth, and whether deeper tissue may be involved

- Nerve sensation, especially if numbness or reduced feeling is present

- Prevention basics

- Do daily skin checks, especially if sensation is reduced

- Protect skin and treat small wounds early, rather than waiting for pain or swelling

- Manage chronic conditions and get help with quitting smoking if that risk factor is in the mix

- After amputation, effective pain control and physical therapy are essential for recovery, with a physical therapist guiding rehabilitation to improve outcomes

If you take only one thing from this section, let it be this: waiting is rarely neutral. Wounds do not always declare themselves dramatic on day one, and that is exactly the problem. Early care keeps options open.

In wound care and recovery, attention to the healing process is crucial, with the intention to restore weight-bearing ability and prepare the residual limb for prosthetic use.

FAQs

What are the most common causes of amputation?

The most common causes often involve long-term disease leading to non-healing wounds, severe infection, and tissue damage. Poor circulation and diabetes complications are major drivers, and trauma is another important cause. Many cases follow either a slow build from chronic disease or a sudden emergency event.

How does poor circulation (PAD/PVD) lead to amputation?

Poor circulation reduces the oxygen and nutrients the tissue needs to heal. When wounds do not heal, infection risk rises, and tissue can become damaged. In severe cases with very low blood flow, tissue can be threatened, and amputation may be needed to remove non-viable tissue safely.

Why does diabetes increase the risk of amputation?

Diabetes can reduce sensation through neuropathy, so injuries may be missed. It can also worsen circulation and slow healing, giving infection more time to spread. That combination is why small wounds and ulcers need fast, consistent care.

Can a small foot sore or blister lead to amputation?

Yes, especially when poor sensation and reduced circulation allow it to worsen unnoticed. Many diabetes-related amputations begin with ulcers that start small and become infected or deep. Early treatment is the best way to keep a minor problem from turning into a major one.

What kinds of infections can lead to amputation?

Severe skin infections, deep tissue infections, and bone infections like osteomyelitis can all increase risk. Some rare infections spread rapidly and require emergency treatment. When infection cannot be controlled or tissue is no longer viable, amputation may be used to stop the spread and protect the rest of the body.

When is amputation needed for cancer or tumors?

Amputation may be considered when removing the entire tumor safely requires taking part of a limb. The surgical goal is complete removal to reduce the chance of regrowth or spread. The final approach depends on tumor type, size, and location, and many cases can use limb-sparing strategies.

What are the early warning signs that a wound is becoming dangerous?

A wound that does not improve, keeps reopening, or changes quickly deserves attention. Spreading redness, swelling, warmth, drainage, fever, and worsening pain can signal escalating infection. Black or gray tissue and a foul odor are urgent warning signs that need prompt evaluation.

What risk factors make amputation more likely?

Diabetes, circulation problems like PAD/PVD, neuropathy, and a history of ulcers or serious infections raise risk. Smoking, uncontrolled blood sugar, and delayed wound care can make outcomes worse. The more risk factors stack up, the more important prevention and early treatment become.

Can amputations be prevented in some cases?

In many cases, yes, especially when risk is driven by chronic disease and delayed care. Daily checks, early treatment of sores, and consistent management of diabetes and circulation-related risks can lower the odds. Prevention is rarely dramatic, but it is often effective.

When should someone seek urgent care for a wound?

Seek urgent care if a wound is rapidly worsening, there is fever, spreading redness, severe pain, drainage, or black or gray tissue. If diabetes or poor circulation is involved, do not wait for the wound to “prove” it is serious. When in doubt, early evaluation is almost always the smarter move.

Conclusion

Amputation is rarely a single moment; it is usually the end of a chain of events. The earlier we catch circulation problems, nerve changes, and infections, the more options we have to protect tissue and prevent complications. That is why the boring steps, daily checks, early treatment, and risk-factor management matter so much.

If there is one message worth keeping, it is this: a non-healing wound deserves respect. We do not have to panic, but we also should not ignore warning signs. Getting care early can change the whole story, and it is one of the most practical forms of prevention we have.

And if amputation is part of someone’s journey, it can be helpful to know that modern prosthetic technology is broad. Some people use simple devices, while others may explore advanced bionic prosthetics such as a bionic hand by Aether Biomedical or a bionic arm, depending on their needs, goals, and clinical guidance.

The earlier we catch circulation problems, nerve changes, and infections, the more options we have to protect tissue and prevent complications. That is why the boring steps, daily checks, early treatment, and risk-factor management matter so much.

If there is one message worth keeping, it is this: a non-healing wound deserves respect. We do not have to panic, but we also should not negotiate with warning signs. Getting care early can change the whole story, and it is one of the most practical forms of prevention we have.

If you’ve got a wound that’s not improving, don’t “wait and see” for another week. Take a clear photo today, note how long it’s been there, and book a check-up. Early care is often the difference between a small problem and a life-changing one.

-2.png?width=352&name=unnamed%20(3)-2.png)